The Burn by Philip Dawkins is an intense, saturated and innovative piece. Like School Girls, or; the African Mean Girls Play by Jocelyn Bioh, The Burn addresses the special sort of bullying high school girls can inflict on each other. Although they have different location and time period settings, there are plenty of other similarities between the pieces. Both proceed with breakneck speed (though The Burn is faster). Both look at the complicated relationship between teachers and students. Finally, both plays share a similar post-modern tragic outlook.

Contents

THE BASICS

TITLE: The Burn

AUTHOR: Philip Dawkins

LICENSING ENTITY: Dramatists Play Service

SUMMARY: During a high school production of The Crucible, mean girls drive their victim to desperate measures.

CHARACTER BREAKDOWN: 4 Females (all high school students, 1 black, 1 white, 1 Latina, 1 any race), 1 Male (30-something white teacher)

COSTUMES: Contemporary

SET REQUIREMENTS: Minimal; desks, chairs, and a door

PROPS: Ordinary objects

STAGING CHALLENGES: Casting may be tricky; all characters are onstage nearly all of the time; SEE the “SUMMARY” and “CONSIDERATIONS” sections below.

BACKGROUND

Philip Dawkins was working as a teaching artist in a Chicago high school when a real-life situation inspired him to write The Burn. Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago premiered The Burn in 2018 as part of their “Steppenwolf for Young Adults” series. The season theme for the 2017-2018 series was “When does a lie become the truth?” and included Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. In addition, Steppenwolf produced a study guide for the play that will be of use to directors considering the piece; it’s styled as social media in several sections. The guide includes an interview with Philip Dawkins, background on and parallels to The Crucible, reading recommendations, real-life connections to The Burn, and class activities for pre- or post-show lessons (with Common Core State Standards indicated!).

SUMMARY

My first reaction to reading the basics of The Burn was that it seemed great for a small, diverse high school. The “Notes on Text” specify that the play is to be done “with as few props and set pieces as possible.” Five cast members means a teacher-director can spend valuable time working with each actor on her character. However, as it often turns out with initial impressions of plays, it’s more complicated than it seems.

The Burn is a great play, and many aspects contribute to its producibility:

- There are 4 strong roles for females, two of them of color.

- Because Arthur Miller’s The Crucible plays a crucial part in The Burn, a teacher-director can make many connections between the English curriculum staple and the production.

- The Burn integrates texting, social media awareness with bullying. Dawkins packs several “hot topics” in educational theatre into a single play.

But there are several challenges for high school production:

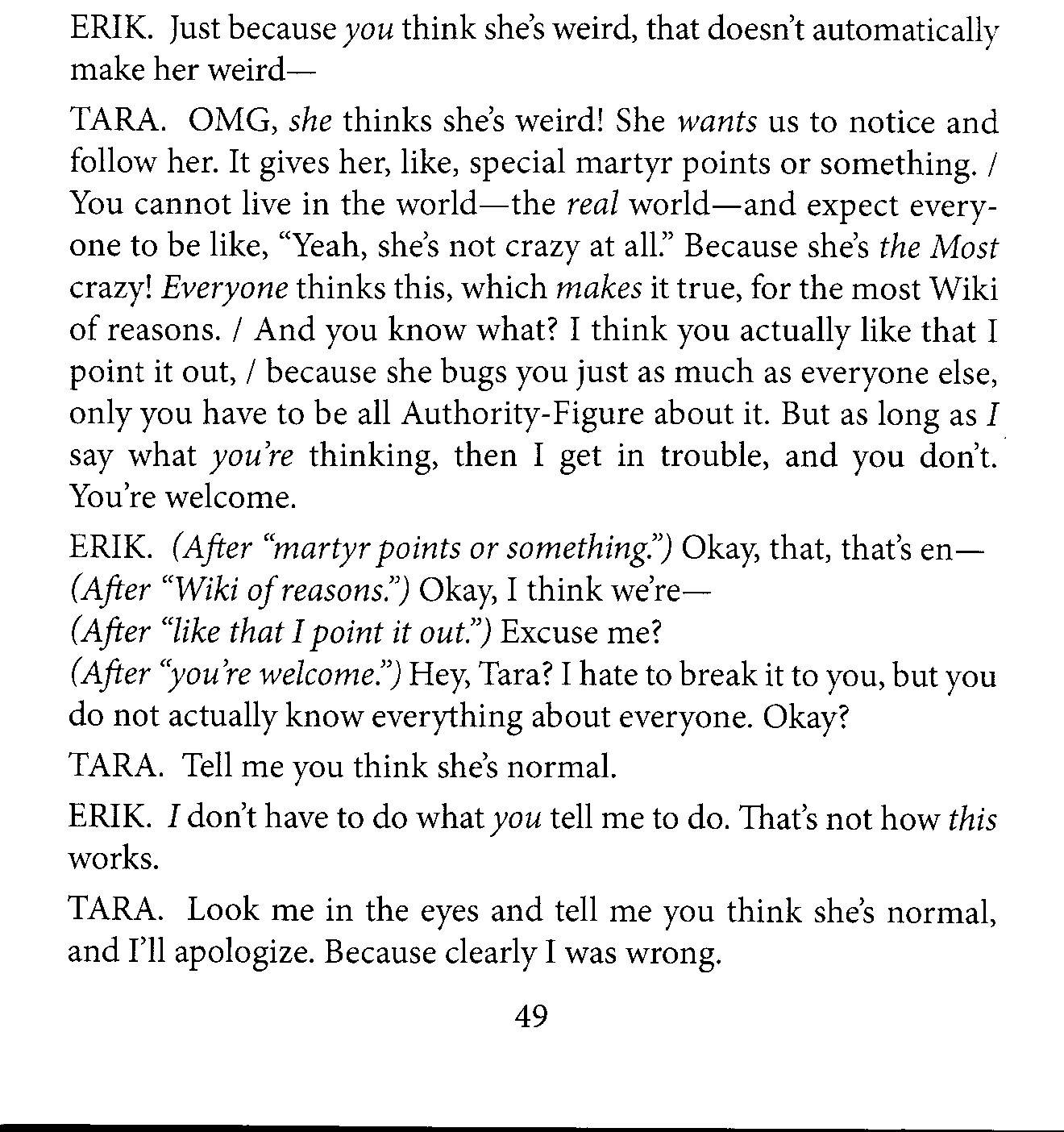

- The dialogue style is rapid-fire and often overlapping, sometimes with four characters’ lines running through each other at once.

- The dialogue happens online, on phones, and in-person, sometimes simultaneously. This poses a challenge for staging, especially because the playwright requests “no miming” for typing or texting.

- There’s a 37-year-old male teacher (ERIK) rounding out the cast of characters. It would require a seriously skilled high school actor to play a character two decades older against his female peers who are playing their own age. In addition, ERIK’s character has the complications being a recovering addict and conflicted Christian. This adds up to an immense performance challenge.

- The play requires a projection screen (and someone to program a series of overlapping social media events.

- This is a play for a teacher-director with A LOT of freedom in production choices; see “CONSIDERATIONS” below.

THE SCRIPT

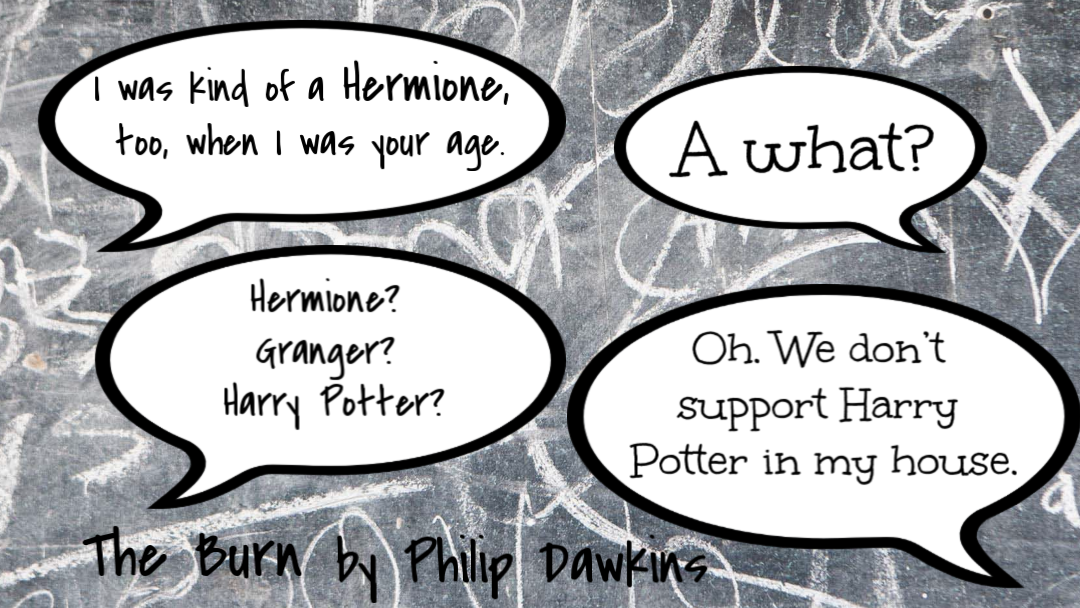

MERCEDES is a new student at a Chicago high school where TARA, ANDI, and SHAUNA make up a mean girl triumvirate. TARA is the “queen bee” of the three, with ANDI as her right-hand minion and SHAUNA playing the Veronica Sawyer to their Heathers. In contrast, MERCEDES is devoutly religious, an evangelist bordering on zealotry, and her parents don’t allow her internet access outside of school. This makes her a magnet for derision, social rejection and cyberbullying, which she isn’t even aware of since she’s not on social media.

The four have an English class with ERIK (“Mr. Krawczeck”), in which they are studying Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. But the play’s not just in the curriculum; it’s that semester’s theatre production. ERIK gets MERCEDES to audition for the play, even though she’s dubious after seeing last semester’s Glass Menagerie: “You made the students in the play take the Lord’s name in vain. A lot.” The “burn” hashtag that TARA, ANDI, and SHAUNA begin using for MERCEDES is #GodHatesMercy.

ERIK casts MERCEDES as Abigail, and SHAUNA as Mary Warren. The two begin to become friendly, if not quite friends. But turnout at the auditions wasn’t great, and when ERIK catches ANDI and TARA plagiarizing their English essays, he gives them the choice of being in the cast of The Crucible, or getting the violation put on their records. This puts them in more frequent contact with MERCEDES, which leads to more bullying.

ERIK attempts to intervene, which makes TARA even more determined to take MERCEDES down. Meanwhile, SHAUNA begins to appreciate MERCEDES, showing her how to get on Instagram and suggesting that MERCEDES doesn’t have to be herself ALL THE TIME. After TARA realizes that ANDI might be interested in her romantically, and SHAUNA is starting to defend MERCEDES, she begins to reject both of them. When ANDI grafittis the #GodHatesMercy hashtag in ERIK’s classroom, and MERCEDES sees it, the fallout leads to another, more serious “burn.”

PAGE-TO-STAGE

My recounting of the plot above only hints at the action and dialogue onstage, both of which are incredibly complicated. Multiple conversations occur simultaneously, sometimes with characters participating in text messaging, social media posts, and IRL exchanges with several characters.

The “Staging Notes” are pretty strict; Dawkins states there should be no blackouts and no unnecessary props or set pieces. He asks for intentionally blurred lines between digital spaces and “IRL.” One of the ways to create the blurring is by creating an “original movement/visual vocabulary” for texting and computer usage.

Dawkins does say: “But, you know, HAVE FUN” at the end of his “Staging Notes.” I feel like it’s “have fun” in a” write-a-Petrarchan-sonnet” kind of way – once you get all the rules down and start writing, you’re able to be more flexible.

The overlapping dialogue requires a lot of annotation – there are slash marks in the lines, and then parts that say “After <THIS WORD>” then delivering the line: The Burn Overlap Text Example[/caption]

The Burn Overlap Text Example[/caption]

There are TWENTY-SEVEN “very quick shifts in time and space” in the 75-page play, which provides opportunities for bold staging choices.

THOUGHTS and QUESTIONS

I’ve assembled some questions and thoughts I have on the play. Given the complex craftmanship that Dawkins applied throughout The Burn, I think that things I’m seeing as confusing/problematic sections are there purposefully. Questions like these are the kinds of things that make for enjoyable exploration in rehearsals!

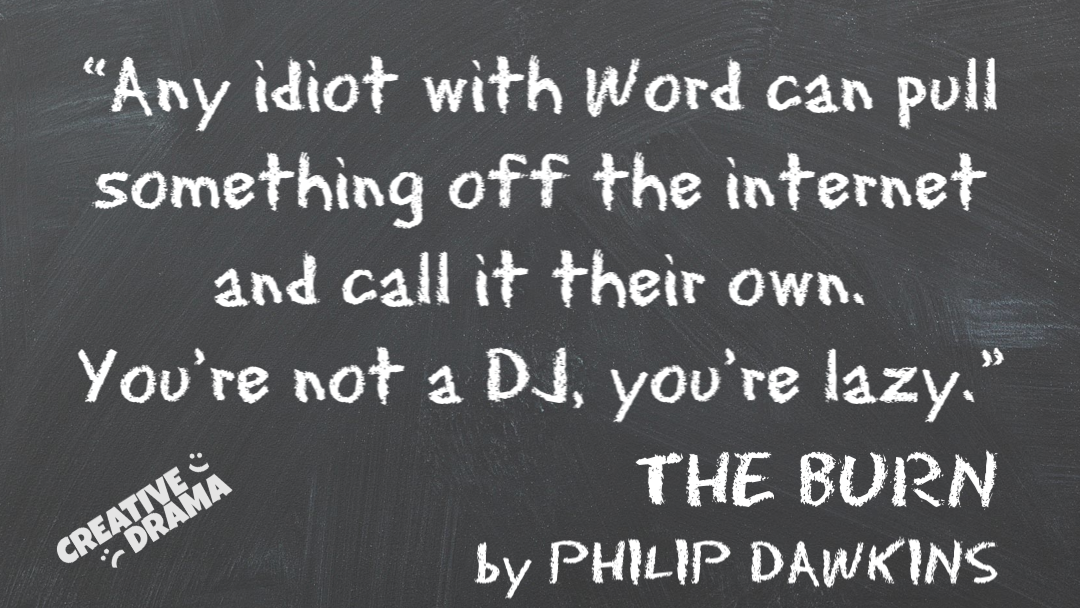

- Why did Dawkins pick The Crucible if he had to paraphrase the lines? It parallels the “remix” justification that TARA and ANDI provide for their plagiarism.

- The plagiarism plot device, which enables ERIK to blackmail (whoops, I mean motivate) TARA and ANDI into doing The Crucible (even though ANDI has to give up basketball to do it), feels gimmicky. But this could be ERIK’s attempt at engineering drama, especially since it’s ERIK’s essay that they (both!) plagiarize, and he planted it on the Internet. “HandItIn.com” sounds a lot like the real-life paper submission site “TurnItIn.com” but on TurnItIn.com, students can’t find, access, and copy other people’s essays, just submit their own. Their teacher then gets a report from the website that flags suspicious segments of submissions. I know there are some adolescents who, out of desperation, or hubris, or stupidity, would do something like this. I think it would be a challenge for the actors playing TARA and ANDI to reconcile how the action fits the characters involved.

- It’s kind of funny that ERIK just did Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie last semester, and now he’s doing The Crucible. It’s possible that ERIK’s required to choose plays that are already in the English curriculum (also possible that Tennessee Williams is a touchstone for the playwright). But as far as appeal to 21st Century potential cast and audience members, these 20th Century classics are a hard sell.

- Also weird: There are 10 male roles and 9 female roles in The Crucible; even if smaller parts were doubled, that’s probably a cast of 12, but there’s no mention of the other cast members. Where’s the student playing Proctor, the main male role in the show? ERIK reads the part during an audition scene (also a little weird).

- Do the actors say “c u” (as written) or “see you?” What performance choices could actors make to indicate the difference?

CONSIDERATIONS

Philip Dawkins wrote The Burn for an audience of young adults; when the piece premiered, the performance featured professional actors.

I’ve been using the “Considerations” section in my Play Overviews to help teacher-directors decide if they’d like to get a hold of a perusal copy of a piece or purchase a script for their classroom/department library. For many educators, administrators, and parents, there are distinctions among what’s acceptable for minors to view/hear, to read, or to perform.

With The Burn, I’d advise teacher-directors to choose it because they know it’s boundary-pushing and their students, program, and community can handle it.

DON’T change the script without permission! See this Dramatists Guild initiative for more information.

#dontchangethewords

LANGUAGE:

- There is profanity, crude sexual references, epithets, and generally “mean” language throughout the play, especially in the lines delivered by TARA, ANDI, and SHAUNA.

- There are many examples of what MERCEDES would call “taking the Lord’s name in vain;” characters say “Oh my God.”

- ANDI, who is white, often uses the slang, diction, and syntax of Black English. TARA, who is black, tells her “It’s kind of offensive” and “no one talks like that. Except for maybe, I don’t know, Eazy-E?”

- TARA, ANDI, and SHAUNA make sexual references about ERIK and imply that MERCEDES is sexually attracted to the teacher.

- ANDI is a lesbian, and she uses a slur to refer to herself, prompting a conversation with TARA and SHAUNA about whether it’s “okay” because it’s her “milieu.” MERCEDES then jumps in to the conversation implying it’s offensive to “gossip” about someone being gay.

VIOLENCE:

- A character is “beaten” onstage – the stage directions say, “This is the moment IRL when MERCEDES is beaten up by the girls, but we won’t see that. We’ll hear it.”

- There are threats of violence both implicit and explicit.

- There are death threats both implicit and explicit.

THE PLAYWRIGHT

Philip Dawkins is a Chicago-based playwright and teacher. He has written over 15 plays and musicals, and won several Jeff Awards (Chicago area theatre honor). He performed his autobiographical play The Happiest Place on Earth as a one-man show.

Dawkins has taught playwriting at Loyola, DePaul, and Northwestern Universities, as well as the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis.

Dawkins has a B.A. in Playwriting from Loyola University Chicago and has had residencies at the William Inge Center for the Arts, the Goodman Theatre’s Playwrights’ Unit, and the MacDowell Colony.

Here’s a list of Dawkins’ plays. He has plays available through Dramatists Play Service and Playscripts.com.

Philip Dawkins is NOT on Twitter. He is on Facebook, though he “only checks it on Fridays.”

OTHER NOTES

Steppenwolf’s production page for The Burn includes a video teaser and photos.

The hub theatre in Washington, D.C. produced The Burn in the Spring of 2019.

The Arizona premiere of The Burn starts November 11, 2019 at BLK BOX PHX. BLK BOX PHX has a study guide for the play.

Here’s a TheatreMania interview with Philip Dawkins. He discusses The Burn and other works.

Loyola University has an alumni profile piece on Dawkins.

Here’s a production of The Crucible at Bedlam Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts that’s not set in 17th-century Salem.